La guerra tra Stati Uniti e Messico (1846-1848)

Sul finire degli anni ’40 del XIX secolo, mentre lungo la volatile frontiera del west scoppiavano numerosi i conflitti tra i coloni che avanzavano e le tribù indiane che erano insofferenti rispetto alla presenza dei bianchi, c’erano altri fronti di guerra pronti per scoppiare in tutta la loro evidenza. Tra questi va’ ricordata la guerra messicano-americana (anche detta “guerra Messico – Stati Uniti”) che scoppiò tra gli Stati Uniti e il Messico nel periodo a cavallo tra il 1846 ed il 1848.

Gli Stati Uniti chiamano questa guerra “la guerra messicana” oppure “guerra di Mr. Polk”, mentre tra i messicani è nota come “Intervento degli Stati Uniti”, “invasione statunitense del Messico” o anche “guerra degli Stati Uniti contro il Messico”. Fin dal nome, quindi, è ben evidente la forte differenza di sensibilità che è sfociata nella guerra.

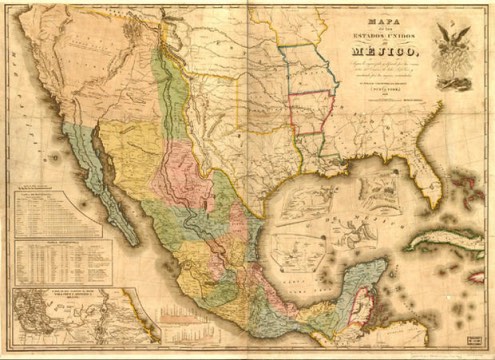

E fu proprio questa differenza di sensibilità, insieme ai molti conflitti irrisolti fra il Messico e la repubblica del Texas, che la guerra messicano-americana trovò il combustile per innescarsi. La repubblica del Texas, infatti, era stata fondata da coloni americani ma… su territorio messicano. Dopo la rivoluzione texana del 1836, il Messico rifiutò ovviamente di riconoscere la Repubblica del Texas ed espresse in maniera decisa e indubitabile l’intenzione di riportare quell’enorme territorio sotto la sua sovranità.

Guerra per il Texas

I più autorevoli tra i coloni del Texas – che erano anche le guide politiche di quelle genti – manifestarono invece interesse per l’annessione agli Stati Uniti, anche se funzionari messicani avvertirono che quella eventuale decisione avrebbe significato automaticamente la guerra.

Trascorsero degli anni in cui gli Stati Uniti si rifiutarono di annettere il Texas, ma nel 1845 il Presidente John Tyler, nell’ultimo giorno del suo mandato, in accordo con la politica espansionista implicita nella cosiddetta “dottrina del destino manifesto” (Manifest Destiny), inviò al Texas un’offerta di annessione che il Texas, ovviamente, accettò e divenne seduta stante il 28° stato degli Stati Uniti. Tale decisione fu anche basata sulla durissima crisi economica nella quale si dibatteva il Texas in quel periodo.

A questo atto unilaterale si oppose il governo messicano che protestò vibratamente affermando che gli Stati Uniti, annettendo una provincia messicana ribelle, erano intervenuti negli affari interni del Messico, ledendone nei fatti la sovranità. Seguirono alcuni tentativi per evitare la guerra che pareva inevitabile. Inviati britannici tentarono ripetutamente di dissuadere il Messico dal dichiarare guerra, ma tali sforzi diplomatici furono infruttuosi, anche perché fra Stati Uniti e Regno Unito scoppiarono altre dispute, in particolare quella sui confini dell’Oregon.

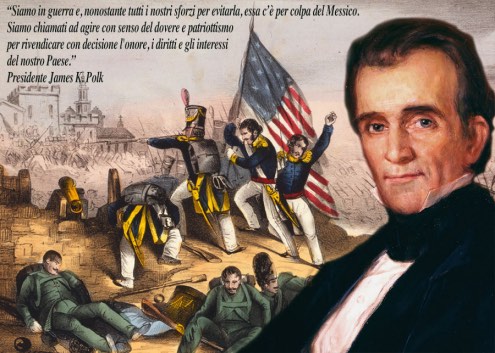

Ad ogni buon conto, va’ detto che furono comunque gli Stati Uniti a dichiarare guerra al Messico, provocando il necessario casus belli.

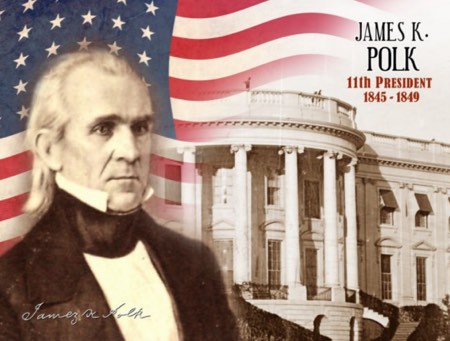

Subito dopo aver compiuto l’annessione del Texas, il neo-eletto presidente James Knox Polk decise di acquistare un’altra provincia messicana, quella della California. Gli espansionisti volevano la California per avere uno sbocco sull’oceano Pacifico, che avrebbe permesso agli Stati Uniti di partecipare al lucroso commercio con l’Asia. Si sapeva, inoltre, che il controllo del Messico su quella provincia lontana era debole, e si temeva che, ritardando l’azione, potesse finire in mano alla Gran Bretagna. Ma, con la dottrina Monroe, gli Stati Uniti avevano espressamente escluso anche solo la possibilità dell’ingerenza di altre potenze nel loro operato nell’intero continente, ritenendola un pericolo per la sicurezza statunitense.

Polk decise così, nel 1845, l’invio in Messico del diplomatico John Slidell per acquistare California e Nuovo Messico per più di 30 milioni di dollari. Nel gennaio 1846 Polk accentuò la pressione sul Messico inviando truppe, al comando del Generale Zachary Taylor, nel territorio allora conteso fra Texas e Messico, tra i fiumi Nueces e Rio Grande. Taylor ignorò le richieste messicane di sgombero e marciò a sud del Rio Grande, dove avviò la costruzione di Fort Texas.

Il viaggio di John Slidell portò il subbuglio nella politica messicana; girava voce che fosse venuto per acquistare altri territori senza offrire nulla per la perdita del Texas. I messicani si rifiutarono di riceverlo, adducendo problemi relativi alle sue credenziali. Così Slidell fece rientro a Washington nel maggio 1846. Il presidente Polk ritenne quel gesto un’offesa e una “causa di guerra più che sufficiente” e si preparò a chiedere al Congresso una dichiarazione di guerra, che il Congresso avrebbe poi ratificato.

Ma gli eventi stavano precipitando e pochi giorni prima che Polk avanzasse la sua richiesta al Congresso, si venne a sapere che forze messicane avevano attraversato il Rio Grande e che avevano ucciso undici soldati statunitensi. Il 24 aprile 1846, infatti, la cavalleria messicana attaccò e catturò il personale di uno dei distaccamenti statunitensi presso il Rio Grande. Dopo questo scontro confinario, battaglie fra le forze messicane e quelle statunitensi scoppiarono a Palo Alto e a Resaca de la Palma.

Al presidente Polk bastò questo per disporre del “casus belli” e in un messaggio al Congresso dell’11 maggio 1846 asserì che il Messico aveva «invaso il nostro territorio e versato sangue statunitense sul suolo statunitense». Logicamente non si soffermò sul fatto che sul territorio in questione esistesse una disputa. Un certo numero di congressisti espresse dubbi circa la versione fornita da Polk dell’accaduto, ma il Congresso approvò a stragrande maggioranza la dichiarazione di guerra, con numerosi Liberali intimoriti dal fatto che la loro opposizione sarebbe loro costata sul piano politico.

La guerra fu dichiarata il 13 maggio 1846.

In linea di massima i congressisti originari del Nord degli Stati Uniti e i Liberali si opponevano alla guerra, mentre tutti quelli originari del Sud degli Stati Uniti e i Democratici erano orientati a sostenerla.

Anche il Messico dichiarò guerra e lo fece il 23 maggio.

Negli Stati Uniti, comunque, non cessarono le polemiche ed i ragionamenti intorno alla dichiarazione di guerra, anche dopo che la guerra fu dichiarata… Infatti, molti Liberali sollevarono obiezioni circa la pretesa di Polk che il Messico avesse «versato sangue statunitense sul suolo statunitense», credendo invece che le forze statunitensi avessero attraversato il Rio Grande al fine deliberato di provocare una guerra contro il Messico. Ma le voci su questo particolare aspetto, dopo la guerra cessarono quasi del tutto.

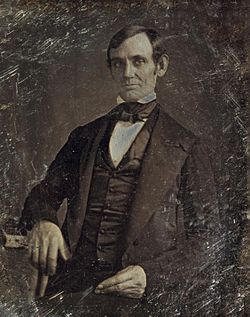

A quel tempo era diventato deputato liberale nella Camera dei Rappresentanti statunitense Abraham Lincoln, che presentò le “Spot Resolutions”, con cui chiese che il Presidente Polk fornisse l’esatta localizzazione di dove il sangue statunitense fosse stato versato. Poiché era un fatto che dei soldati statunitensi erano stati uccisi, tuttavia, queste risoluzioni furono ampiamente ignorate.

Abramo Lincoln nel 1846

Abramo Lincoln nel 1846

Fin da allora gli storici hanno discusso se Polk avesse o meno deliberatamente provocato la guerra, o se la sua politica del “rischio calcolato” gli fosse sfuggita di mano.

Sappiamo per certo che il Messico non era preparato ad una guerra perché il paese si trovava allora nella rovina economica, ma anche politica e sociale. In più, l’esercito e i suoi comandanti non erano armati e preparati per difendere il paese, dato che mancavano armi, uniformi, scorte alimentari e persino un sano spirito di lotta per difendere almeno gli interessi della propria patria. I fucili messicani erano vecchi e i cannoni – che erano tutti vecchi e a corto raggio – portavano la data della guerra d’indipendenza, mentre i soldati statunitensi avevano fucili di ultima generazione e cannoni a lunga gittata. Va anche ricordato che i soldati messicani venivano reclutati con il sistema della leva ed erano scarsamente ricompensati oltre che malnutriti, mentre quelli americani appartenevano ad un vero esercito professionale ed erano volontari pagati dal governo e ricevevano puntualmente il loro stipendio.

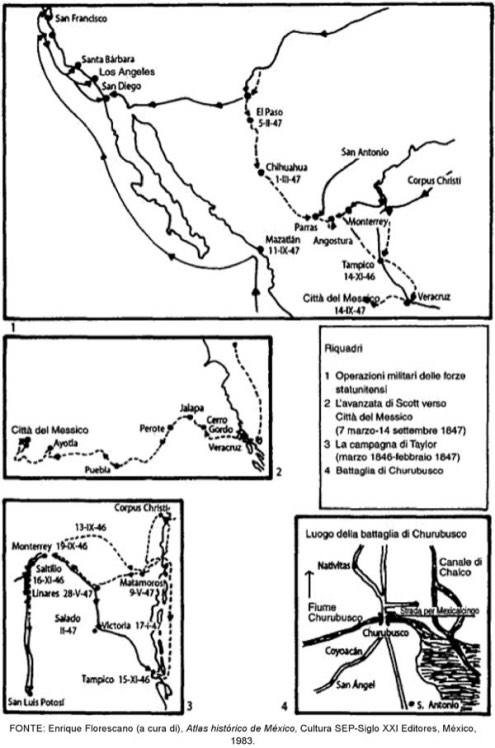

Immediatamente dopo la dichiarazione di guerra, le forze armate statunitensi invasero il territorio messicano su più fronti.

Un episodio particolarmente “forte” quanto a capacità di aumentare la confusione fu quello accaduto il 14 giugno 1846 quando i coloni inglesi a Sonoma arrestarono e imprigionarono il locale governatore, dichiarando una repubblica indipendente della California.

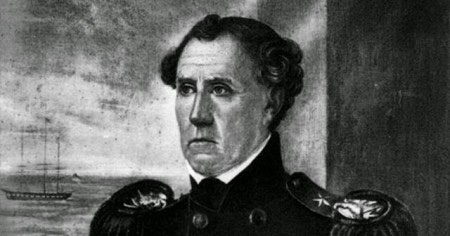

Gli Stati Uniti non restarono certo alla finestra, dato che era più che noto il loro interesse all’annessione formale della California, perciò per presidiare il fronte del Pacifico, la marina statunitense inviò John D. Sloat ad occupare la California e la dichiarò appartenente agli Stati Uniti in base alla considerazione che i britannici avrebbero anche potuto tentare di occupare l’area. Sloat assunse il comando di Sonoma e Monterey nel luglio di quell’anno.

John D. Sloat, inviato ad occupare la California

Sul fronte meridionale della guerra al Messico, l’esercito americano – quello che viene solitamente chiamato Army of the West (Esercito d’Occidente) -, alla guida di Stephen W. Kearny, occupava Santa Fe, nel Nuovo Messico. Kearny inviò anche un piccolo contingente in California dove, dopo qualche iniziale rovescio, riuscì a unirsi ai rinforzi della Marina al comando di Robert F. Stockton e a occupare gli importantissimi snodi urbani di San Diego e Los Angeles. A causa delle contrastanti direttive provenienti da Washington, un importante dissenso scoppiò fra Kearny e Stockton sul controllo della California. Stockton nominò John C. Frémont governatore della California, mentre Kearny si autonominò per quell’incarico. A prevalere fu Kearny e Frémont venne arrestato e inviato davanti alla Corte Marziale per la sua lealtà nei confronti di Stockton in quella disputa.

La componente più grossa delle truppe americane, quella guidata da Taylor, continuò ad agire lungo il Rio Grande, vincendo la battaglia di Monterey nel settembre 1846, dopo lunghe settimane di battaglia. Nel frattempo lo stato dello Yucatan si era dichiarato nuovamente indipendente e questo produsse un sollevamento a Città del Messico, cosa che portò il governo di Mariano Paredes a chiedere il ritorno di Antonio López de Santa Anna dal suo esilio cubano. Santa Anna eluse il blocco navale americano e nel dicembre del 1846 formò un nuovo governo con Valentin Gomez Farias come vicepresidente.

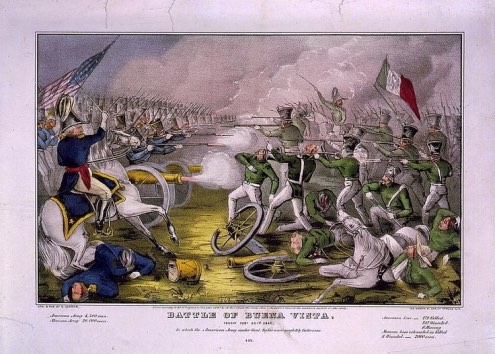

Antonio López de Santa Anna marciò personalmente verso nord per combattere Taylor, ma fu sconfitto nella battaglia di Buena Vista il 22 febbraio 1847. Santa Anna lasciò Farias come presidente ad interim, inoltre promulgò una legge che permetteva al governo federale di appropriarsi dei beni della Chiesa cattolica per un valore di 15 milioni di pesos.

Ma, di fronte a questo affronto, il popolo di Città del Messico si sollevò in armi e assediò il presidente nel Palazzo Nazionale, così Santa Anna si vide costretto a trasformare il decreto in una donazione volontaria del clero di 100.000 pesos.

Nel frattempo, invece di rafforzare l’esercito di Taylor per consentirgli di progredire nell’avanzata, il presidente Polk inviò un secondo esercito sotto il Generale Winfield Scott in marzo, trasportato nel porto di Veracruz per via mare, per avviare un’invasione del cuore stesso del Messico. Scott si affermò nell’assedio di Veracruz e prese Puebla senza sparare un solo colpo, grazie anche all’intervento della Chiesa cattolica che convinse i propri fedeli ad accogliere l’esercito invasore come un esercito liberatore. Successivamente Scott marciò alla volta di Città del Messico con l’aiuto della Mexican Spy Company (un gruppo di ladri e banditi che combatterono con gli americani). Le spie furono le guide che aiutarono a vincere le battaglie di Cerro Gordo e Chapultepec, grazie anche all’incompetenza di Santa Anna, che ordinò di non fortificare i monti intorno, il che diede agli americani l’opportunità di avanzare.

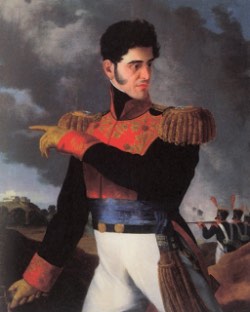

Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio López de Santa Anna

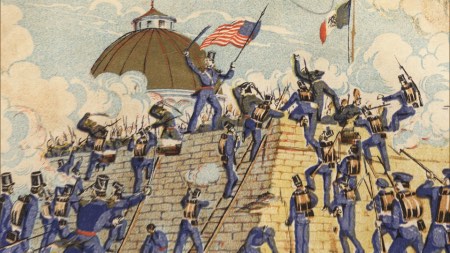

Dopo le importanti battaglie di Padierna, Churubusco e Molino del Rey, Chapultepec cadde, non senza prima aver combattuto valorosamente. I giovani cadetti dell’accademia militare morirono valorosamente, e sono infatti ricordati come niños héroes (ragazzi eroici). La caduta di Chapultepec ebbe due conseguenze immediate: l’occupazione da parte degli statunitensi di Città del Messico e la nuova rinuncia di Santa Anna alla presidenza.

Il trattato di Cahuenga, firmato il 13 gennaio 1847, mise fine ai combattimenti in California. Il trattato di Guadalupe Hidalgo, sottoscritto il 2 febbraio 1848, concluse la guerra e dette agli Stati Uniti il controllo assoluto del Texas, come pure della California, del Nevada, dello Utah, e di parti del Colorado, Arizona, Nuovo Messico e Wyoming. In cambio il Messico ricevette 18.250.000 dollari, l’equivalente dei 627.500.000 dollari (valore di metà anno 2000) dei costi della guerra.

Nel corso della guerra, circa 13.000 americani morirono. Di questi, solo 1.700 circa caddero in azione di combattimento; le altre perdite furono provocate dai disagi e dalle condizioni sanitarie assolutamente precarie. Le perdite messicane rimangono un mistero, ma sono stimate a 25.000.

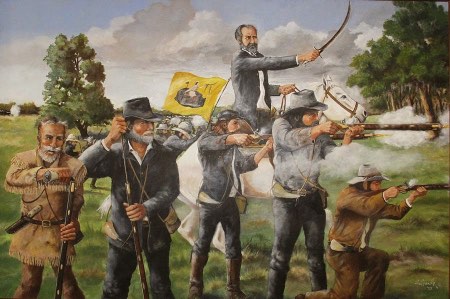

Soldati provenienti dal Tennessee nella guerra con il Messico

Nel corso della guerra furono combattute molte battaglie importanti, incluse la battaglia di Churubusco e quella di Padernia. Il comandante messicano dell’epoca era Pedro María Anaya, che difese il convento di Santa María Churubusco e che pronunciò quella che più tardi sarebbe stata considerata la più famosa frase della guerra, riferita allorché il generale Twiggs entrò nel convento: «Se avessimo munizioni, voi non sareste qui».

Il Battaglione San Patricios fu un gruppo di varie centinaia di soldati irlandesi immigrati, che disertarono dalle file americani per raggiungere l’esercito messicano. Molti furono uccisi nella Battaglia di Churubusco, mentre circa 100 furono catturati e impiccati come disertori.

L’ultimo veterano americano del conflitto, Owen Thomas Edgar, morì il 3 settembre 1929 all’età di 98 anni.

A causa e conseguentemente alla guerra, il Messico perse il 55% dei suoi territori, che seppur ben risarciti (con l’equivalente di 550.450.600 euro odierni) vennero annessi con duraturo rancore agli Stati Uniti. Tuttavia la guerra accentuò il sentimento di unità nazionale in Messico, un elemento che era andato perso da quando il movimento indipendentistico messicano s’era dissolto nel 1821. Il conflitto provocò inoltre una drastica perdita di autorevolezza da parte del generale Santa Anna, che dal 1833 esercitava poteri assoluti sul Paese. Una nuova generazione di politici infatti riuscirà a strappare il Messico dal suo controllo e successivamente a proclamare uno stato liberale e democratico nel 1857. Uno dei primi atti del governo repubblicano liberale fu l’adozione di numerose leggi che facilitarono e stimolarono la colonizzazione di vasti territori spopolati degli Stati settentrionali del Messico. Dietro le leggi che agevolavano tale colonizzazione vi era precisamente l’idea di evitare ulteriori amputazioni territoriali.

Si deve anche considerare che i territori annessi dagli Stati Uniti ospitavano migliaia di famiglie messicane. Alcune di esse scelsero di tornare in Messico, mentre altre scelsero di rimanere sotto il governo degli gli Stati Uniti, visto che il trattato di Guadalupe Hidalgo conteneva garanzie di concessione della cittadinanza a costoro e di lotta alla povertà. Gli Stati Uniti e il Messico nel 1889 costituirono una Commissione delegata a risolvere i casi riguardanti le comuni frontiere e il controllo delle acque.

Gli Stati Uniti, per via della grande vittoria riportata a conclusione della guerra, videro crescere enormemente il sentimento patriottico, esattamente come stava accadendo con l’acquisizione dei territori del West. Il governo stava infatti acquisendo la metà meridionale dell’Oregon, dando la sensazione che la fede dei cittadini nel loro Paese si stesse accrescendo (e riaffermando il concetto espresso nel “Destino manifesto”).

Il periodo di euforia nazionale e nazionalistica, tuttavia, non durò a lungo perché il peso della guerra era stato ampiamente sostenuto dagli Stati del Sud e evitato o contrastato dagli Stati del Nord. Questo amplificò notevolmente il problema della schiavitù degli Stati Uniti, che venne esacerbato anche dal fatto che il Texas riconobbe l’istituzione della schiavitù, mentre il Messico non la accettava. Numerosi abolizionisti nordisti videro la guerra come un tentativo dei proprietari di schiavi di espandere la schiavitù ed assicurarsi un’influenza continua nel governo federale. Nel 1846 il congressista David Wilmot promosse la “Wilmot Proviso” per proibire la schiavitù in ogni nuovo territorio strappato al Messico. La proposta di Wilmot non passò ma anche questa fu una scintilla che appiccò il fuoco più tardi fra le opposte visioni intorno allo schiavismo.

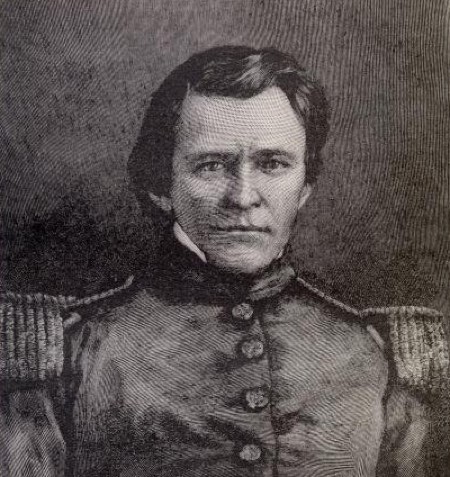

Ulysses S. Grant al tempo della guerra con il Messico

In seguito, Ulysses S. Grant, che servì nella guerra sotto il comando di Scott, avrebbe descritto il conflitto come una guerra di conquista per l’espansione della schiavitù, preludio pertanto della guerra di secessione: «La ribellione dei Sudisti fu largamente il frutto della guerra col Messico. Le nazioni, come le persone, sono punite per le loro trasgressioni. Noi abbiamo avuto la nostra punizione con la più sanguinosa e costosa guerra dei tempi moderni».

Oltre a Grant, molti dei generali che si distinsero nella guerra di secessione parteciparono a questa guerra: George B. McClellan, Ambrose E. Burnside, “Stonewall” Jackson, James Longstreet, George G. Meade e Robert E. Lee, così come il futuro Presidente confederato, Jefferson Davis.

Allegato: Dichiarazione originale di guerra al Messico

James K. Polk, President of the United States at Washington, D.C., to the Congress of the United States. A special message calling for a declaration of war against Mexico.

Washington, May 11, 1846.To the Senate and the House of Representatives:

The existing state of the relations between the United States and Mexico renders it proper that I should bring the subject to the consideration of Congress. In my message at the commencement of your present session, the state of these relations, the causes which led to the suspension of diplomatic intercourse between the two countries in March, 1845, and the long-continued and unredressed wrongs and injuries committed by the Mexican Government on citizens of the United States in their persons and property were briefly set forth.

As the facts and opinions which were then laid before you were carefully considered, I can not better express my present convictions of the condition of affairs up to that time than by referring you to that communication.

The strong desire to establish peace with Mexico on liberal and honorable terms, and the readiness of this Government to regulate and adjust our boundary and other causes of difference with that power on such fair and equitable principles as would lead to permanent relations of the most friendly nature, induced me in September last to seek the reopening of diplomatic relations between the two countries. Every measure adopted on our part had for its object the furtherance of these desired results. In communicating to Congress a succinct statement of the injuries which we had suffered from Mexico, and which have been accumulating during a period of more than twenty years, every expression that could tend to inflame the people of Mexico or defeat or delay a pacific result was carefully avoided. An envoy of the United States repaired to Mexico with full powers to adjust every existing difference. But though present on Mexican soil by agreement between the two Governments, invested with full powers, and bearing evidence of the most friendly dispositions, his mission has been unavailing. The Mexican Government not only refused to receive him or listen to his propositions, but after a long-continued series of menaces have at last invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our own soil.

It now becomes my duty to state more in detail the origin, progress, and failure of that mission. In pursuance of the instructions given in September last, an inquiry was made on the 13th of October, 1845, in the most friendly terms, through our consul in Mexico, of the minister for foreign affairs, whether the Mexican Government “would receive an envoy from the United States intrusted with full powers to adjust all the questions in dispute between the two Government, ” with the assurance that “should the answer be in the affirmative such an envoy would be immediately dispatched to Mexico. The Mexican minister on the 15th of October gave an affirmative answer to this inquiry, requesting at the same time that our naval force at Vera Cruz might be withdrawn, lest its continued presence might assume the appearance of menace and coercion pending the negotiations. This force was immediately withdrawn. On the 10th of November, 1845, Mr. John Slidell, of Louisiana, was commissioned by me as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary of the United States to Mexico, and was intrusted with full powers to adjust both the questions of the Texas boundary and of indemnification to our citizens. The redress of wrongs of our citizens naturally and inseparably blended itself with the question of boundary. The settlement of the one question in any correct view of the subject involves that of the other. I could not for a moment entertain the idea that the claims of our much-injured and long-suffering citizens, many of which had existed for more than twenty years, should be postponed or separated from the settlement of the boundary question.

Mr. Slidell arrived at Vera Cruz on the 30th of November and was courteously received by the authorities of that city. But the Government of General Herrera was then tottering to its fall. The revolutionary party had seized upon the Texas question to effect or hasten its overthrow. Its determination to restore friendly relations with the United States, and to receive our minister to negotiate for the settlement of this question, was violently assailed, and was made the great theme of denunciation against it. The Government of General Herrera, there is good reason to believe, was sincerely desirous to receive our minister; but it yielded to the storm raised by its enemies, and on the 21st of December refused to accredit Mr. Slidell upon the most frivolous pretexts. These are so fully and ably exposed in the note of Mr. Slidell of the 24th of December last to the Mexican minister of foreign relations, herewith transmitted, that I deem it unnecessary to enter into further detail on this portion of the subject.

Five days after the date of Mr. Slidell’s note General Herrera yielded the Government to General Paredes without a struggle, and on the 30th of December resigned the Presidency. This revolution was accomplished solely by the army, the people having taken little part in the contest; and thus the supreme power in Mexico passed into the hands of a military leader.

Determined to leave no effort untried to effect an amicable adjustment with Mexico, I directed Mr. Slidell to present his credentials to the Government of General Paredes and ask to be officially received by him. There would have been less ground for taking this step had General Paredes come into power by a regular constitutional succession. In that event his administration would have been considered but a mere constitutional continuance of the Government of General Herrera, and the refusal of the latter to receive our minister would have been deemed conclusive unless an intimation had been given by General Paredes of his desire to reverse the decision of his predecessor. But the Government of General Paredes owes its existence to a military revolution, by which the subsisting constitutional authorities had been subverted. The form of government was entirely changed, as well as all the high functionaries by whom it was administered.

Under these circumstances, Mr. Slidell, in obedience to my direction, addressed a note to the Mexican minister of foreign relations, under date of the 1st of March last, asking to be received by that Government in the diplomatic character to which he had been appointed. This minister in his reply, under date of the 12th of March, reiterated the arguments of his predecessor, and in terms that may be considered as giving just grounds of offense to the Government and people of the United States denied the application of Mr. Slidell. Nothing therefore remained for our envoy but to demand his passports and return to his own country.

Thus the Government of Mexico, though solemnly pledged by official acts in October last to receive and accredit an American envoy, violated their plighted faith and refused the offer of a peaceful adjustment of our difficulties. Not only was the offer rejected, but the indignity of its rejection was enhanced by the manifest breach of faith in refusing to admit the envoy who came because they had bound themselves to receive him. Nor can it be said that the offer was fruitless from want of opportunity of discussing it; our envoy was present on their own soil. Nor can it be ascribed to a want of sufficient powers; our envoy had full powers to adjust every question of difference. Nor was there room for complaint that our propositions for settlement were unreasonable; permission was not even given our envoy to make any proposition whatever. Nor can it be objected that we, on our part, would not listen to any reasonable terms of their suggestion; the Mexican Government refused all negotiation, and have made no proposition of any kind.

In my message at the commencement of the present session I informed you that upon the earnest appeal both of the Congress and convention of Texas I had ordered an efficient military force to take a position “between the Nueces and Del Norte.” This had become necessary to meet a threatened invasion of Texas by the Mexican forces, for which extensive military preparations had been made. The invasion was threatened solely because Texas had determined, in accordance with a solemn resolution of the Congress of the United States, to annex herself to our Union, and under these circumstances it was plainly our duty to extend our protection over her citizens and soil.

This force was concentrated at Corpus Christi, and remained there until after I had received such information from Mexico as rendered it probable, if not certain, that the Mexican Government would refuse to receive our envoy.

Meantime Texas, by the final act of our Congress, had become an integral part of our Union. The Congress of Texas, by its act of December 19, 1836, had declared the Rio del Norte to be the boundary of that Republic. Its jurisdiction had been extended and exercised beyond the Nueces. The country between that river and the Del Norte had been represented in the Congress and in the convention of Texas, had thus taken part in the act of annexation itself, and is now included within one of our Congressional districts. Our own Congress had, moreover, with great unanimity, by the act approved December 31, 1845, recognized the country beyond the Nueces as a part of our territory by including it within our own revenue system, and a revenue officer to reside within that district had been appointed by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. It became, therefore, of urgent necessity to provide for the defense of that portion of our country. Accordingly, on the 13th of January last instructions were issued to the general in command of these troops to occupy the left bank of the Del Norte. This river, which is the southwestern boundary of the State of Texas, is an expose frontier. From this quarter invasion was threatened; upon it and in its immediate vicinity, in the judgement of high military experience, are the proper stations for the protecting forces of the Government. In addition to this important consideration, several others occurred to induce this movement. Among these are the facilities afforded by the ports at Brazos Santiago and the mouth of the Del Norte for the reception of supplies by sea, the stronger and more healthy military positions, the convenience for obtaining a ready and a more abundant supply of provisions, water, fuel, and forage, and the advantages which are afforded by the Del Norte in forwarding supplies to such posts as may be established in the interior and upon the Indian frontier.

The movement of the troops to the Del Norte was made by the commanding general under positive instructions to abstain from all aggressive acts toward Mexico or Mexican citizens and to regard the relations between that Republic and the United States as peaceful unless she should declare war or commit acts of hostility indicative of a state of war. He was specially directed to protect private property and respect personal rights.

The Army moved from Corpus Christi on the 11th of March, and on the 28th of that month arrived on the left bank of the Del Norte opposite to Matamoras, where it encamped on a commanding position, which since been strengthened by the erection of fieldworks. A depot has also been established at Point Isabel, near the Brazos Santiago, 30 miles in rear of the encampment. The selection of his position was necessarily confided to the judgment of the general in command.

The Mexican forces at Matamoras assumed a belligerent attitude, and on the 12th of April General Ampudia, then in command, notified General Taylor to break up his camp within twenty-four hours and to retire beyond the Nueces River, and in the event of this failure to comply with these demands announced that arms, and arms alone, must decide the question. But no open act of hostility was committed until the 24th of April. On that day General Arista, who had succeeded to the command of the Mexican forces, communicated to General Taylor that “he considered hostilities commenced and should prosecute them.” A party of dragoons of 63 men and officers were on the same day dispatched from the American camp up the Rio del Norte, on its left bank, to ascertain whether the Mexican troops had crossed or were preparing to cross the river, “became engaged with a large body of these troops, and after a short affair, in which some 16 were killed and wounded, appear to have been surrounded and compelled to surrender.

The grievous wrongs perpetrated by Mexico upon our citizens throughout a long period of years remain unredressed, and solemn treaties pledging her public faith for this redress have been disregarded. A government either unable or unwilling to enforce the execution of such treaties fails to perform one of its plainest duties.

Our commerce with Mexico has been almost annihilated. It was formerly highly beneficial to both nations, but our merchants have been deterred from prosecuting it by the system of outrage and extortion which the Mexican authorities have pursued against them, whilst their appeals through their own Government for indemnity have been made in vain. Our forbearance has gone to such an extreme as to be mistaken in its character. Had we acted with vigor in repelling the insults and redressing the injuries inflicted by Mexico at the commencement, we should doubtless have escaped all the difficulties in which we are now involved.

Instead of this, however, we have been exerting our best efforts to propitiate her good will. Upon the pretext that Texas, a nation as independent as herself, thought proper to unite its destinies with our own, she has affected to believe that we have severed her rightful territory, and in official proclamations and manifestoes has repeatedly threatened to make war upon us for the purpose of reconquering Texas. In the meantime we have tried every effort at reconciliation. The cup of forbearance had been exhausted even before the recent information from the frontier of the Del Norte. But now, after reiterated menaces, Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at war.

As war exists, and, notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it, exists by the act of Mexico herself, we are called upon by every consideration of duty and patriotism to vindicate with decision the honor, the rights, and the interests of our country.

Anticipating the possibility of a crisis like that which has arrived, instructions were given in August last, “as a precautionary measure” against invasion or threatened invasion, authorizing General Taylor, if the emergency required it, to accept volunteers, not from Texas only, but from the States of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky, and corresponding letters were addressed to the respective governors of those States. These instructions were repeated, and in January last, soon after the incorporation of “Texas into our Union of States,” General Taylor was further “authorized by the President to make a requisition upon the executive of that State for such of its militia force as may be needed to repel invasion or to secure the country against apprehended invasion.” On the 2d day of March he was again reminded, “in the event of the approach of any considerable Mexican force, promptly and efficiently to use the authority with which he was clothed to call to him such auxiliary force as he might need.” War actually existing and our territory having been invaded, General Taylor, pursuant to authority vested in him by my direction, has called on the governor of Texas for four regiments of State troops, two to be mounted and two to serve on foot, and on the governor of Louisiana for four regiments of infantry to be sent to him as soon as practicable.

In further vindication of our rights and defense of our territory, I invoke the prompt action of Congress to recognize the existence of the war, and to place at the disposition of the Executive the means of prosecuting the war with vigor, and thus hastening the restoration of peace. To this end I recommend that authority should be given to call into the public service a large body of volunteers to serve for not less than six or twelve months unless sooner discharged. A volunteer force is beyond question more efficient than any other description of citizen soldiers, and it is not to be doubted that a number far beyond that required would readily rush to the field upon the call of their country. I further recommend that a liberal provision be made for sustaining our entire military force and furnishing it with supplies and munitions of war.

The most energetic and prompt measures and the immediate appearance in arms or a large and overpowering force are recommended to Congress as the most certain and efficient means of bringing the existing collision with Mexico to a speedy and successful termination.

In making these recommendations I deem it proper to declare that it is my anxious desire not only to terminate hostilities speedily, but to bring all matters in dispute between this Government and Mexico to an early and amicable adjustment; and in this view I shall be prepared to renew negotiations whenever Mexico shall be ready to receive propositions or to propositions of her own.

I transmit herewith a copy of the correspondence between our envoy to Mexico and the Mexican minister for foreign affairs, and so much of the correspondence between that envoy and the Secretary of State and between the Secretary of War and the general in command on the Del Norte as is necessary to a full understanding of the subject.JAMES K. POLK.